Elisabeth Rousset or Boule de Suif

A Reflection on Maupassant, Identity, and the Art of Labeling

Literature Reflection Philosophy

2nd November, 2025

I started reading de Maupassant in 9th grade. There was a story of his, translated into Bengali, about a necklace about how Matilda was so utterly absorbed in it, yet so blind to the world around her. Perhaps material attraction is just too powerful for anyone to resist. But was it specifically a trait of women’s desire, or is it something universal? We love to label things; it seems almost in our nature. And once we label, we proudly declare that we are not part of it, that we belong only to all that is “good.” But what does it even mean to be good? Who decides?

I started reading Boule de Suif on the train. I wasn’t sure if I’d be able to finish it on time, since managing time has always been hard for me mostly because I waste so much of it doing absolutely nothing. Maybe that’s why I decided to be a little productive for once, even if just for 35 minutes trying to do something instead of staring out the window. There’s nothing new to see anyway. I’ve been traveling from Akadem to the city for almost a year now, and nothing ever really changes. Especially in winter everything looks the same, as if a thick white blanket has quietly covered the world.

And I can’t even stare at my co-travelers. What would they think? Though, perhaps they’re having the same thoughts. Most of them are glued to their phones, scrolling endlessly as if there’s no real reason to use it, yet still doing it for the next forty minutes without a break. A few people just close their eyes. I think they’re the most peaceful ones. I wish I could do that but I’m not good at it. Somehow, it feels awkward. So reading seems like the best option for me. At first, I thought Boule de Suif might be some romantic writing that was my initial impression when I started reading. However, it is a bit difficult to understand in the first one or two pages, as it seems to mix themes of war and romance.

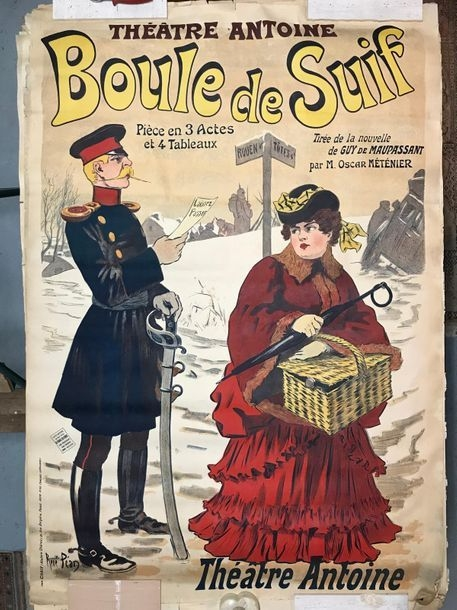

Back to the story Elizabeth Rousset, our main protagonist, is a kind-hearted and patriotic woman, nicknamed “Boule de Suif” because of her plump figure (the name literally translates to “ball of fat”). So, she is a prostitute traveling with a group of bourgeois passengers fleeing the Prussian invasion during the Franco-Prussian War. Despite the disdain the others show her because of her profession, Elizabeth stands out for her generosity and courage — sharing her food and standing firm in her principles. There is no doubt she is a moral woman. Long story short, when a Prussian officer demands her favors as the price for allowing the group to continue their journey, she initially refuses to compromise her dignity. But under pressure, she sacrifices herself for the group’s sake. In the end, she is rejected and shunned by the very people she helped.

Now, what I really wanted to share is my opinion about how Guy de Maupassant chose to use the name Boule de Suif instead of Elizabeth (or Elisabeth) Rousset. In the story, Maupassant uses the nickname “Boule de Suif” around 30 to 40 times, maybe even more. I didn’t count exactly, but I have a pretty clear idea. It’s the main way the protagonist is identified throughout the story. In contrast, her real name, Elizabeth Rousset, appears only about three times that I’m quite sure of. And here’s the thing worth noticing is that this sharp difference isn’t random. It highlights the very social phenomenon Maupassant is critiquing.

Where I grew up, almost everyone had a nickname. It usually came from something about how they looked, what they did in the past, or their profession , sometimes even just a random quirk about their appearance. I still remember my father calling a close family friend by his nickname. It was a funny one, really there was nothing wrong with the man; he was perfectly fine and well-built. But my father used to call him by a word that actually meant “petty thief.” Curious, I once asked my father what it meant. He laughed and said that the man used to steal fruits when he was young, and from then on, everyone in the village started calling him by that name. It was funny at first, but over time, it just stuck. And I believe it’ll be really hard for anyone to separate that nickname from his identity now. One thing was clear , if you did something great, your name would carry that greatness too. If you had the heart of a lion, you became the “lion-hearted.” Not wrong, actually — just look at Richard the Lionheart or Catherine the Great of Russia. But our protagonist, Elizabeth, was on the opposite side of that, unfortunately.

This naming pattern in the story clearly shows how women like Elizabeth are often reduced to labels defined by their physical appearance or social role rather than their individuality. It’s hard to hold on to your own sense of self when society has already “categorized” you based on your profession or status. Here, Elizabeth becomes a powerful metaphor. We’re still practicing the same norms, labeling people and boxing them into identities and honestly, I believe it’s something very hard to change. It’s clear that Maupassant uses this contrast to reveal the hypocrisy of social norms and class prejudice. The rare mention of Elizabeth’s real name marks those brief moments when her true identity and humanity manage to break through the layers of stereotype that society has placed on her.

So, I guess we’ve mastered the art of labeling things. Maybe the harder question now is — can we ever stop?

Novosibirsk, Russia